W

hen Tim Berners-Lee wrote his proposal for an information management system at CERN, the European particle physics laboratory, it was out of frustration that the different parts of the organisation – both human and technological – struggled to communicate with each other.

Data was hard to find, there were multiple, incompatible computer systems, and knowledge was not shared efficiently.

Nearly three decades later, the World Wide Web that Berners-Lee imagined has transformed how we communicate and the way we live our lives – and yet improving coordination within companies remains one of the business world’s most stubborn challenges.

Why? Because it is a problem that technology alone cannot fix. When organisations are successful in getting their people to work together effectively, it is not because they have a common IT infrastructure, intranet or cloud-based file-sharing system, but because they have solved a complex equation of which technology is just a part – alongside leadership, motivation, incentives, structure, process, culture, communication and more.

This is difficult to do, and in large firms that do not operate under a single brand, it is even more difficult.

Take WPP. As a company that has grown – to a significant degree – through acquisition, the Group is made up of many individual agency brands that, traditionally, have operated largely independently from one another. Each has its own identity, its own way of doing things, its own relationships with clients.

This has been a source of great strength for those companies and for the Group as a whole, and will continue to be so. But it can also be a barrier to communication and collaboration between WPP’s constituent parts.

Once upon a time this would not have mattered very much. It wasn’t important to clients, so it wasn’t important to us. But clients’ needs have changed – and marketing services businesses need to change to meet them.

Advertisers or clients increasingly tell us that they want to take advantage of the full scale and capabilities of WPP, to receive a tailor-made range of integrated communications services, and to tap into our talent and resources wherever they sit within the Group.

WPP’s 205,000+ individual brains represent the planet’s greatest store of marketing services insight, expertise, creativity and experience

Some especially forward-thinking clients began asking for this over 10 years ago. It was clear that, as well as serving them through single agencies (each organised as a separate, ‘vertical’ silo), we needed a ‘horizontal’ offering that spanned the entire Group. We needed to stimulate co-operation across company, functional and national boundaries, and we needed to share information much more effectively. And so something we call ‘horizontality’ was born.

Connected know-how

Horizontality is best described as ‘connected know-how’: a way of working that unites people with diverse skills to deliver seamless solutions for clients. We have made it our first strategic priority, because client demand for coordination between the different companies and disciplines within parent groups is growing stronger all the time. We need to continue to do it better than our competitors, several of whom have now woken up to its advantages.

Including those of our associates and investments, WPP’s 205,000+ individual brains represent the planet’s greatest store of advertising and marketing services insight, expertise, creativity and experience. The more we work together, the more we can draw on that collective intelligence, and the more effective we are on behalf of our clients as a result.

So how do we connect all that know-how, and deploy all that talent?

Horizontality takes various forms, ranging from relatively small-scale collaborations between different agencies and specialisms around the world to its most advanced manifestation: the Global Client Team.

Global Client Teams pull together people and resources from across WPP’s companies, disciplines and markets to provide the most creative and effective solutions for a single client’s business. The model is infinitely flexible, with each Team built around the client’s unique needs.

All Teams have a dedicated leader, who provides a single point of leadership and access to WPP’s collective talent and capabilities. This allows clients to pull from the best of the best, from anywhere within the Group.

WPP pioneered the Team model of client service, beginning with Ford and HSBC over a decade ago. Ford, through GTB (Global Team Blue) and Colgate, through Red Fuse, are the most complete examples today. There are now 48 Global Client Teams, accounting for more than a third of WPP’s total revenues and involving almost 40,000 of our people.

Another important integrator is the Country Manager, whose job is to encourage horizontality in specific geographic markets in order to deliver the best resources to clients, to identify acquisition opportunities and to help recruit local talent. We currently have WPP Country and Regional Managers covering about half of the 112 countries in which we operate.

We have also established a number of sector-specific WPP practices and other cross-Group units, through which our companies share knowledge, pool resources and coordinate services for clients. They include The Store (retail), WPP Digital, The Government & Public Sector Practice, The Data Alliance, WPP Health & Wellness and, most recently, The WPP Sports Practice.

WPP Health & Wellness is particularly significant as it represents the first time in our history that an operating company has carried the WPP brand. Comprising all of our healthcare agencies, pharmaceutical and consumer healthcare client teams, and new horizontal health partnerships across all the Group’s major companies, it breaks new ground by going to market explicitly under the WPP banner.

WPP united

We will continue to travel in this direction, behaving less and less as a loose federation of independent companies, and more and more as one, united firm.

This will be particularly pronounced in our media investment and data investment businesses, GroupM and Kantar, which between them represent approximately half of the Group’s revenues.

WPP Health & Wellness breaks new ground by going to market explicitly under the WPP banner

When we have been successful in winning big pitches over the last year or so, it was because we presented a tightly integrated offer, with media and data in lockstep alongside creative and strategy. And when we failed to present an integrated offer, we failed to win the business.

We are unique among our industry peers in having our own data business. Our ability to leverage that proprietary first-party data and apply our insights to the media investment we make on clients’ behalf, and to our wider business, is a source of value to those clients and competitive advantage to us.

For some, the idea of ‘one WPP’ is controversial. We certainly can’t push agencies down this road too fast. It needs to be a gradual process, handled with great care. Controversial or not, though, such integration is inevitable if we are to retain our place as essential partners to brands. As Marc Pritchard, Procter & Gamble’s chief brand officer, put it when addressing agencies at an industry conference last year: “Your complexity should not be our problem.”

With ever greater frequency, global clients are conducting reviews and calling pitches at the level of parent company rather than individual networks or agencies. Those with the most joined-up, comprehensive offer, and who present it most compellingly, will be the winners in this new landscape.

The collaborative instinct

The large majority of people within our agencies don’t, in fact, need much pushing.

Tim Berners-Lee’s proposal wasn’t just a response to a problem – it was a hopeful vision of what might be possible. He identified not only the need for a better approach, but the potential of an idea based on essential truths about human nature.

“CERN is a wonderful organisation,” he wrote. “It involves several thousand people, many of them very creative, all working toward common goals. Although they are nominally organised into a hierarchical management structure, this does not constrain the way people will communicate, and share information, equipment and software across groups.”

He also said his best source of information was often asking people what they were working on while they were having a coffee break – which if nothing else shows that particle physics is as reliant on caffeine and gossip as our own business.

His point was that you don’t have to force people to collaborate – they do it naturally. The challenge, then, is to facilitate that collaboration, and to remove those things that stop it happening.

For our people, horizontality provides exposure to, and the opportunity to work with, a wider range of colleagues and clients across a broader spectrum of marketing disciplines. This is particularly the case in our new colocations, such as the WPP Campus in Shanghai, which bring the Group’s agencies together under one roof in a single, beautifully designed, ultra-modern building. Madrid and Amsterdam are next, with more to follow.

Informal interaction and networks are critical to organisations of all kinds, and our new shared office spaces are specifically designed to enable the open, face-to-face exchange of ideas and information (including conversations over coffee) that help people do their best work.

In a group of our size and international spread, virtual spaces are, of course, vital for collaboration too.

In 2014, we began a major program of transformation and investment in our global information technology systems. Many of our operating companies now share a common IT infrastructure and set of applications. If this sounds a little underwhelming, consider that for the first 30 years of our existence, most of WPP’s companies had their own, often proprietary systems that (like some agency CEOs) resolutely refused to talk to each other.

Happily, in both cases, that no longer applies. For the first time, there is a single email and calendar platform, a directory with the details of everyone within the Group and a common file-sharing application. Simple things that have a huge impact on how we all work together.

Team Unilever, which handles one of our biggest global client relationships, has taken advantage of these shared platforms with the launch of Central, a new community and publishing platform for the 15,000 people and 80 different agencies working on Unilever business worldwide.

It is a tool not only for sharing news and information but also for building a greater sense of cohesion, understanding what colleagues are working on and, critically, sourcing talent and expertise. Expect to see more initiatives like this among our other client teams.

Horizontality within

Horizontality is happening not only between our companies but within them.

In January 2017, Ogilvy & Mather, the global marketing communications network, unveiled a transformation program that will see the company unified as a single-branded, fully integrated enterprise, Ogilvy. The reorganisation will simplify both how the company markets itself around the world and its own internal structure.

Like all WPP businesses, Ogilvy’s essential offering is the quality of its talent, and the company’s ‘One Ogilvy’ strategy is designed to ensure that its people are able to work together as seamlessly as possible.

In September 2016, Kantar, our data investment business, launched a new corporate identity covering its 12 operating brands, reflecting its own ongoing change program. As well as creating a single family of brands, the program fosters and rewards much greater collaboration between them, with the aim of presenting clients with more easily-navigable and connected solutions that draw on the best of Kantar’s expertise.

And in November 2016, GroupM, the parent company to our media agencies, announced the creation of [m]PLATFORM, the industry’s most advanced technology suite of media planning applications, data analytics and digital services.

Horizontality is happening not only between our companies but within them

The platform brings together – under one team – capabilities from GroupM and other WPP businesses, including search, social, mobile, digital ad operations and programmatic. It connects wide-ranging WPP data sources across Kantar and Wunderman; third-party data providers; GroupM’s data from unique agreements with global media partners; and clients’ own data when they choose.

[m]PLATFORM is supported by a team of data scientists, technologists and digital practitioners from GroupM specialist companies and Xaxis, our programmatic digital media platform, and it allows media planners at all GroupM agencies to use the most detailed consumer data to achieve results for their clients.

Worldwide communications services expenditure 2016 $m

Worldwide communications services expenditure 2016 $m

|

Advertising

|

Data investment management

|

Public

relations

|

Direct & specialist communications

|

Sponsorship

|

Total

|

|

North America

|

188,675

|

19,640

|

4,300

|

109,681

|

22,400

|

344,696

|

| Latin America

|

36,412

|

1,800

|

480

|

38,084

|

4,500

|

81,276

|

| Europe

|

105,569

|

16,800

|

2,700

|

114,759

|

15,900

|

255,728

|

| Asia Pacific

|

176,515

|

6,000

|

4,950

|

61,442

|

14,800

|

263,707

|

| Africa & Middle East

|

17,414

|

760

|

158

|

2,204

|

2,600

|

23,136

|

|

Total

|

524,585

|

45,000

|

12,588

|

326,170

|

60,200

|

968,543

|

Media and marketing investment vs GDP 2012-2017

% change

- Media and marketing annual % change

- Global nominal GDP % change

A model for our times

One of the reasons that clients are increasingly attracted to WPP’s horizontal, Team model of service is the efficiencies of scale we are able to offer. In today’s low-growth, cost-constrained corporate world, this is becoming ever more important.

Since the financial crisis, heralded by the collapse of Lehman Brothers nearly a decade ago, top-line growth has been hard to come by, boards and investors have been ultra-conservative, and companies have been reluctant to invest.

As a result we have seen a much greater focus on cost reduction, consolidation on a massive scale, the widespread stockpiling of cash, and a boom in share buy-backs and dividends.

By one measure, at least, corporate America is shrinking. In 2009, 60% of earnings across the S&P 500 were spent on share buy-backs and dividends. That ratio passed 100% at the beginning of 2015, and rose to 131% in the first quarter of 2016. In the FTSE 100, the dividend-payout ratio has climbed from below 40% in 2011 to over 70% in 2016.

Worldwide, corporate investment as a proportion of GDP has continued to decline. In the US, fixed capital investment by business is at its lowest ebb for more than 60 years. Companies are, consequently, sitting on huge amounts of uninvested cash. McKinsey & Company estimate that corporate cash holdings are the equivalent of 10% of GDP in the US, 22% in Western Europe and 47% in Japan.

What all this tells us is that companies lack the will or, perhaps, the confidence to invest in their own growth and development, and prefer instead the seemingly risk-free approach of returning funds to shareholders or retaining ever-larger cash balances.

By choosing short-term risk-avoidance, though, they are piling up far greater dangers for the future. Long-term success relies on investment in those things that drive a business forward – brands, research and development, innovation and marketing.

The pressure faced by leaders to manage their businesses for short-term results is intense. The number of listed firms in the US has halved in the last 20 years, driven by consolidation and the pursuit of savings. In 1990, there were 11,500 M&A deals worldwide; since 2008, the number has more than doubled to 30,000 a year, with a value equivalent to approximately 3% of global GDP.

So-called legacy companies are squeezed from all sides – by activist investors, by zero-based budgeters, and by new, disruptive competitors. Analysts and the financial press, meanwhile, obsess over the minutiae of quarterly results as if they were the key to a company’s entire future, rather than a snapshot of its fortunes over a mere three months.

Shape of global recovery

% change

- Advertising

- Global nominal GDP

Nominal GDP projections 2016-2018f

% change

Short-termism on the rise

In a 2013 McKinsey survey of more than 1,000 top executives, nearly two-thirds said that pressure to deliver short-term financial performance had increased in the prior five years, and nearly 90% agreed that “a longer time horizon to make business decisions” would boost corporate performance.

The potential value unlocked by companies taking a longer-term approach was worth more than $1 trillion in forgone US GDP over the last decade

When the exercise was repeated in 2016, the situation had deteriorated further. Whereas, in 2013, 79% felt under particular pressure to demonstrate results within two years or less, by 2016 that figure had risen to 87%.

The 2016 study identifies the vicious circle of short-termism that makes it such a difficult disease to cure: “While executives may feel that investor pressure forces their hand, the short-term objectives and metrics they set also push investors to shorten their horizons to match the data available to them.”

CEOs have complained of this for some time, but until now there has been little evidence to support their case. In February this year, McKinsey published a new piece of research led by Dominic Barton, the firm’s global managing partner. It identified US companies that take the long view and found that, between 2001 and 2014, their revenue grew on average 47% more than that of other firms; their earnings grew 36% more; and their profit grew 81% more.

Long-term companies invested almost 50% more in research and development; their market capitalisation grew $7 billion more than that of other businesses; their total shareholder return was greater; and they added nearly 12,000 more jobs on average.

The report lays bare the cost of short-termism: “Had all firms created as many jobs as the long-term firms, the US economy would have added more than five million additional jobs over this period… this suggests, on a preliminary basis, that the potential value unlocked by companies taking a longer-term approach was worth more than $1 trillion in forgone US GDP over the last decade.”

McKinsey is one of the founders, alongside the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, of Focusing Capital on the Long Term – an initiative aimed at promoting long-term thinking in business and investment, that we also support.

In September 2016, with BlackRock, The Dow Chemical Company and Tata Sons, the founding partners relaunched the scheme as FCLT Global, an independent not-for-profit with its own CEO. FCLT Global is part of a growing movement to raise awareness of the damaging effects of short-termism and develop strategies for defeating it.

Late last year, US educational and policy studies organisation The Aspen Institute assembled leaders from global businesses including Unilever, Pfizer, Royal Dutch Shell, Levi Strauss and WPP to launch The American Prosperity Project – “a non-partisan framework for long-term investment.”

The launch was a call to action not only for business leaders but also policymakers, recognising that progress is impossible without partnership between the public and private spheres. As The Aspen Institute puts it, “Neither business nor government can shoulder this responsibility alone.”

Average job creation: long-term vs others

Annual cumulative jobs added

Average company economic profit: long-term vs others

$ million per year

- Long-term

- All others

- Financial crisis

Inherent unpredictability

Central to the Aspen project is spending on infrastructure, chiming with President Trump’s plans to invest $1 trillion in “transportation, clean water, a modern and reliable electricity grid, telecommunications, security infrastructure, and other pressing domestic infrastructure needs” (to quote from the campaign literature).

Not for the first time, residents of the Davos bubble (of which I am one) had misjudged the public mood, failing at the previous meeting to predict the result of either the US election or the Brexit vote

If these plans become reality, they are likely to boost growth and inflation, perhaps delivering a two- to three-year Keynesian/Trumpian boom. But what we gain on the US domestic swings we may lose on the international roundabouts, given the inherent unpredictability of President Trump’s impact overseas. The ‘Muslim travel ban’ and suspension of the US refugee program provided an early and particularly vivid example of that. Large question marks also hang over the US approach to Russia, China, Mexico and NATO, to name just a few examples, adding further clouds to an already uncertain outlook for business globally.

The wave of populism that swept President Trump to power, dumped (or is in the process of dumping) the UK out of the European Union and rocked the Establishment the world over was the single most fretted-over phenomenon for delegates at the World Economic Forum in January 2017.

Not for the first time, residents of the Davos bubble (of which I am one) had misjudged the public mood, failing at the previous meeting to predict the result of either the US election or the Brexit vote.

Although I thought Hillary Clinton would emerge as the winner, as the Primaries got under way I wrote that “Davos is a long way from the heartlands of America, where dissatisfaction with the political Establishment runs deep. The economic crisis, recession, unemployment, wage stagnation and so-called ‘hollowing-out’ of the middle classes that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 have opened the door to populists… Trump showed he can translate celebrity into votes… he has tapped into something very important that cannot be ignored.”

As President, Donald Trump continues to tap that well of public discontent. Alongside controlling immigration, job creation and job repatriation are at the top of the President’s list of promises to the American people. Globalisation has been the bogeyman but there are other, perhaps more fundamental, threats to employment.

Principal contributors to 2017 media growthf

| |

Contribution

$m

|

Contribution

%

|

|

ASIA PACIFIC (all)

|

11,064

|

48.2

|

|

NORTH ASIA

|

6,634

|

28.9

|

|

China

|

6,242

|

27.2

|

|

NORTH AMERICA

|

4,979

|

21.7

|

|

US

|

4,684

|

20.4

|

|

WESTERN EUROPE

|

2,785

|

12.1

|

|

LATIN AMERICA

|

2,360

|

10.3

|

|

UK

|

1,553

|

6.8

|

|

Argentina

|

1,426

|

6.2

|

|

Japan

|

1,355

|

5.9

|

|

ASEAN

|

1,349

|

5.9

|

|

CENTRAL & EASTERN EUROPE

|

1,144

|

5.0

|

|

India

|

1,063

|

4.6

|

|

MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA

|

631

|

2.7

|

|

Russia

|

533

|

2.3

|

|

Egypt

|

496

|

2.2

|

|

Australia

|

482

|

2.1

|

|

Philippines

|

428

|

1.9

|

|

Brazil

|

372

|

1.6

|

|

Spain

|

349

|

1.5

|

|

Thailand

|

330

|

1.4

|

|

Vietnam

|

328

|

1.4

|

|

South Korea

|

312

|

1.4

|

|

Turkey

|

303

|

1.3

|

|

Canada

|

295

|

1.3

|

|

Indonesia

|

266

|

1.2

|

|

Mexico

|

213

|

0.9

|

Contributions to 2017 media growth by region/countryf $m

Robots and robber barons

At the beginning of 2017, I attended the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas – a highly-polished showcase for everything from the latest smartphone, TV and in-car technology to virtual and augmented reality, artificial intelligence robotics and home automation. But beneath the buzz surrounding the toys and gadgets, there was serious discussion of the potentially darker implications of technology’s ubiquity.

Voices as diverse as Stephen Hawking, Citibank and the University of Oxford have warned of the risks of automation to human employment. Subject to the constraints of economic viability, most things that can be automated will be automated. One study has suggested that 35% of UK jobs face being replaced by robots, a figure that rises to almost 50% in the US and 77% in China.

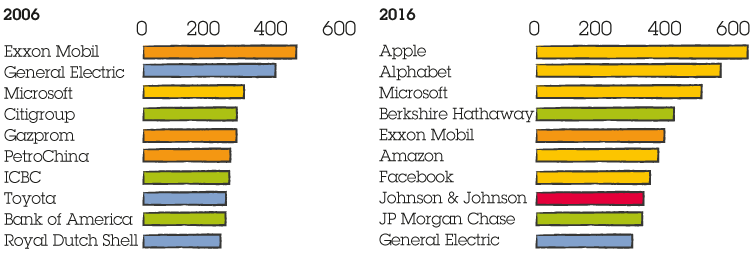

At the same time, a new breed of corporation has grown to dominate the business landscape. There have always been very large companies, of course, but today’s big beasts are different.

World’s largest listed companies by market capitalisation 2006 vs 2016* $bn

- Energy

- Financials

- Healthcare

- Industrials

- IT

A recent report in The Economist highlights the issue: “In Silicon Valley a handful of giants are enjoying market shares and profit margins not seen since the robber barons in the late 19th century... In the old days companies with large revenues and global footprints almost always had lots of assets and employees. Some superstar companies, such as Walmart and Exxon, still do. But digital companies with huge market valuations and market shares typically have few assets.”

The report points out a startling contrast: a quarter of a century ago, the three biggest automotive manufacturers in Detroit had nominal revenues of $250 billion, a market capitalisation of $36 billion and 1.2 million employees; in 2014 the three biggest players in Silicon Valley had revenues of $247 billion, were capitalised at over $1 trillion and had just 137,000 people on their books.

The tech giants have ushered in an era of massive scale accompanied by minimal employment. Expect the debate to get louder as this trend accelerates.

Tech companies faking it?

The digital duopoly enjoyed by Google and Facebook is the most striking aspect of the contemporary media business landscape. Their dominance and influence has brought scrutiny – and criticism.

Facebook was forced to admit to a series of embarrassing errors after it repeatedly overstated the metrics used to gauge the effectiveness of advertising, prompting wider questions about the value of digital ad spend in a market already dogged by concerns over viewability, third-party verification and fraud.

More damagingly, along with Twitter and Google it was thrust into the limelight during the fractious US Presidential campaign, accused of giving a platform to hatred and fake news, and even of swaying the result itself. The long-standing collective defence to such claims is that they are not media companies but tech companies – a defence that’s wearing pretty thin.

Google and Facebook are, after all, the largest and third largest recipients of our media spend on behalf of clients, at around $5 billion and $1.7 billion respectively in 2016 (the second largest is 20th Century Fox/News Corp/Sky at $2.25 billion). That’s a lot of media bought from organisations who claim not to be media owners.

Although they masquerade as tech, they are in the business of monetising inventory, just like any traditional media group. Unlike them, however, they seek to disassociate themselves from the content on which they rely, claiming to be mere digital plumbers with little or no responsibility for what flows through their pipes. They are finding this line increasingly difficult to hold.

As Robert Thomson, chief executive of News Corp, put it: “These companies are in digital denial. Of course they are publishers and being a publisher comes with the responsibility to protect and project the provenance of news. The great papers have grappled with that sacred burden over decades and centuries, and you can’t absolve yourself from that burden or the costs of compliance by saying, ‘We are a technology company’.”

Digital advertising in the spotlight

Media agencies have also faced questions over their role in a less-than-perfect digital inventory supply chain, and their supposed complicity in a system that supports questionable content rather than quality publishing.

Increasing automation has brought advertisers significant benefits in terms of greater efficiencies and better targeting but, in the digital and programmatic world, there is a risk of advertising appearing in inappropriate contexts, of bots notching up fraudulent views and of ads being paid for but hardly seen.

Given these risks, GroupM has taken a very public, proactive leadership role in championing viewability, anti-fraud and brand safety measures. No one has fought harder to ensure quality in digital advertising.

GroupM is the only media investment business with a dedicated global team focused on digital supply chain integrity. It uses every available brand safety tool and supports or leads every industry effort that drives up standards in the digital media marketplace. It helped found and fund the Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG) and other initiatives that benefit the industry as a whole. And it has developed trusted marketplaces, outside open networks, where advertising is placed only with well-known, safe media partners who do not carry fake news or hate speech.

GroupM has shown that with the right mitigation strategy and by working with the best technology partners, it is possible to ensure that the overwhelming majority of advertising is published alongside contextually relevant and appropriate media content.

Brand safety measures are, however, only as good as the oversight and coding of content by the digital media owners themselves, who have ultimate responsibility for what appears on their platforms. To take YouTube as an example, if Google fails to correctly identify video content, it becomes impossible for advertisers to completely exclude risk when buying online inventory.

As the neutral intermediary between brands and media owners, GroupM will continue to work with all parties to drive continual improvement in this still very young and fast-developing market.

Growth of media in major markets 2012-2017f %

| Internet |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

10.3 |

9.8 |

12.1 |

11.5 |

8.4 |

9.2 |

| Latin America |

27.1 |

38.2 |

n/a3 |

60.4 |

n/a3 |

17.1 |

| Western Europe |

11.5 |

9.7 |

11.4 |

11.9 |

12.3 |

10.6 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

29.3 |

21.7 |

11.8 |

13.6 |

16.3 |

14.4 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

24.5 |

26.9 |

27.0 |

27.4 |

23.4 |

18.2 |

| North Asia1 |

39.2 |

39.4 |

34.6 |

33.9 |

27.8 |

20.7 |

| ASEAN2 |

60.1 |

57.0 |

55.3 |

49.0 |

32.0 |

23.9 |

| Middle East & Africa |

57.0 |

5.9 |

34.9 |

8.8 |

7.3 |

6.4 |

| World |

15.5 |

15.4 |

16.6 |

17.9 |

14.6 |

13.3 |

| Television |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

3.9 |

0.9 |

3.5 |

-0.1 |

3.9 |

1.9 |

| Latin America |

8.3 |

19.7 |

9.7 |

4.5 |

5.8 |

5.2 |

| Western Europe |

-6.1 |

-0.5 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

3.0 |

1.5 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

2.3 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

-2.9 |

7.9 |

8.4 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

5.7 |

4.4 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

-0.4 |

0.6 |

| North Asia1 |

5.8 |

3.0 |

-1.8 |

-2.8 |

-4.6 |

-4.4 |

| ASEAN2 |

13.8 |

16.5 |

10.9 |

15.4 |

6.3 |

11.2 |

| Middle East & Africa |

12.5 |

7.5 |

-8.2 |

21.0 |

7.0 |

6.6 |

| World |

3.7 |

3.8 |

2.9 |

1.8 |

2.8 |

2.2 |

| Outdoor |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

3.7 |

3.2 |

0.1 |

2.0 |

3.1 |

3.0 |

| Latin America |

12.2 |

2.2 |

5.0 |

24.4 |

50.7 |

26.4 |

| Western Europe |

-2.7 |

-1.9 |

-0.1 |

4.7 |

2.9 |

2.5 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

3.1 |

2.8 |

-0.4 |

-10.7 |

5.6 |

6.5 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

12.0 |

4.9 |

6.3 |

0.0 |

3.3 |

3.0 |

| North Asia1 |

18.5 |

5.9 |

8.7 |

-0.8 |

3.5 |

3.8 |

| ASEAN2 |

17.8 |

6.0 |

-3.1 |

-1.0 |

9.7 |

6.0 |

| Middle East & Africa |

26.5 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

6.2 |

2.5 |

0.4 |

| World |

7.3 |

2.9 |

3.6 |

1.7 |

5.1 |

4.2 |

| Magazines |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

1.9 |

0.0 |

-4.3 |

-3.2 |

-2.5 |

-3.3 |

| Latin America |

0.0 |

-3.2 |

-9.0 |

-8.2 |

2.3 |

-4.6 |

| Western Europe |

-10.3 |

-8.7 |

-5.5 |

-6.2 |

-5.4 |

-4.6 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

-4.1 |

-11.5 |

-10.7 |

-19.8 |

-9.3 |

-6.5 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

0.0 |

-2.6 |

-7.6 |

-8.1 |

-12.6 |

-9.8 |

| North Asia1 |

4.7 |

-1.8 |

-12.3 |

-16.6 |

-29.0 |

-23.9 |

| ASEAN2 |

-1.8 |

-5.6 |

-10.0 |

-8.2 |

-15.8 |

-9.5 |

| Middle East & Africa |

-12.7 |

6.3 |

-11.8 |

-12.5 |

-13.0 |

-8.3 |

| World |

-1.6 |

-2.5 |

-5.4 |

-5.0 |

-4.4 |

-4.4 |

| Radio |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

4.4 |

0.1 |

-3.5 |

-1.6 |

3.2 |

2.6 |

| Latin America |

2.5 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

4.7 |

0.6 |

2.2 |

| Western Europe |

-2.9 |

-2.3 |

2.7 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.0 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

8.5 |

2.6 |

2.2 |

-5.1 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

4.9 |

-2.4 |

3.4 |

4.9 |

-0.3 |

-0.2 |

| North Asia1 |

7.1 |

1.5 |

2.1 |

6.2 |

-6.3 |

-6.6 |

| ASEAN2 |

9.5 |

-25.5 |

6.4 |

10.3 |

4.3 |

6.3 |

| Middle East & Africa |

35.3 |

5.1 |

-9.1 |

-1.7 |

-1.9 |

3.5 |

| World |

4.2 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

| Cinema |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

4.5 |

4.3 |

-16.7 |

15.0 |

0.0 |

4.3 |

| Latin America |

-1.4 |

15.5 |

21.3 |

25.5 |

-10.2 |

-1.3 |

| Western Europe |

3.2 |

-10.8 |

-2.8 |

13.9 |

2.6 |

3.6 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

9.8 |

10.5 |

-2.9 |

1.1 |

6.7 |

4.5 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

12.0 |

-8.3 |

-2.9 |

18.5 |

13.3 |

11.4 |

| North Asia1 |

0.0 |

4.2 |

4.0 |

0.0 |

-4.8 |

-5.0 |

| ASEAN2 |

11.8 |

-27.7 |

-13.9 |

19.3 |

6.9 |

6.5 |

| Middle East & Africa |

-0.1 |

2.0 |

-32.6 |

19.0 |

11.0 |

5.7 |

| World |

4.7 |

-5.2 |

-1.7 |

16.1 |

3.2 |

4.9 |

| Newspapers |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016f |

2017f |

| North America |

-4.8 |

-4.0 |

-5.9 |

-7.3 |

-9.3 |

-8.6 |

| Latin America |

3.5 |

6.9 |

-1.7 |

1.5 |

-3.5 |

3.4 |

| Western Europe |

-9.9 |

-10.1 |

-5.4 |

-6.8 |

-5.7 |

-6.0 |

| Central & Eastern Europe |

-1.4 |

-9.0 |

-9.2 |

-7.7 |

-4.7 |

-3.6 |

| Asia Pacific (all) |

-2.4 |

-2.9 |

-7.8 |

-12.0 |

-12.2 |

-7.4 |

| North Asia1 |

-5.1 |

-5.1 |

-15.0 |

-26.7 |

-31.9 |

-24.1 |

| ASEAN2 |

1.5 |

8.0 |

-7.2 |

-6.0 |

-10.1 |

-4.3 |

| Middle East & Africa |

-4.9 |

-0.1 |

-12.2 |

-16.2 |

-10.8 |

-7.6 |

| World |

-5.1 |

-4.7 |

-6.6 |

-8.6 |

-8.9 |

-6.6 |

Enduring strength

There are those who point to the rise of adtech and martech, the walled gardens of Facebook and Google, and the growing interest in our sector of acquisitive management consultancy firms, and would have you believe that we are in a period of unprecedented change or even existential threat to the advertising and marketing services business. This argument is somewhat lacking in supporting data.

The direction of the wind always changes, and WPP has always had a very good weather vane. Ours is a history of rapidly and successfully adapting our existing businesses by developing or acquiring new skills to meet the changing needs of the market and our clients.

Walled gardens are not a new phenomenon. The US TV giants were once as powerful oligopolists as the current generation of digital media firms are today. In media planning and buying, our role has always been to extract maximum value from media platforms on behalf of advertisers to help them achieve their objectives – that hasn’t changed.

Advertisers rely on us for objective assessment of the value of those different platforms. Google and Facebook both think they have all the answers, but they can’t both be right. Clients know this, and although some work direct with media owners some of the time, very few work direct all of the time.

At WPP we have a range of capabilities that any single advertiser would find it very difficult to replicate in-house. We are expert in managing data and systems that can be applied to advertising; we work with every media platform everywhere in the world; we have visibility across all channels and all product and service categories globally; we have deep institutional knowledge in every business sector in a world of high talent mobility on the client side; and we are uniquely well placed to stay abreast of the myriad product and technology changes in the market.

In contrast, consulting businesses are flawed by their lack of geographic reach, their lack of exposure across channels and their lack of exposure in a meaningful way to media markets. If you don’t trade in the product it’s hard to understand it.

Adtech and martech products are complex to choose, use and change. We play a vital role in selection, implementation, operation and – most crucially – in managing switching between components. This expertise stems from the fact that WPP has always been an early adopter of technology and its application to marketing services. Our rapid deployment and integration of technology has created new opportunities in many of our businesses (from GroupM and Xaxis to Wunderman and AKQA) and enduring relevance and strength for WPP itself.

And what of creativity, the heart of our business? In today’s disrupted, technology-driven market, demand for creative services remains as strong as ever. Or, more simply, there’s still no substitute for a brilliant idea for a campaign. And there is no organisation on earth with more people who excel at producing such ideas than WPP.

Our record at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, where we have been named the most creative group for the last six years, is testament to that, while our five consecutive Effies, recognising the effectiveness of marketing campaigns, proves the business value of such creative excellence to clients.

If anything, the need for creative talent has grown rather than diminished. New channels require new assets and formats, boosting demand for agencies, individuals and teams that can produce platform-specific work.

Fuel in the tank

WPP is the leader in our industry but scale has value only when it is harnessed. We have done that very effectively for many years in some parts of the Group, not least in our media division GroupM, but we have yet to do so fully in other areas of our business. In other words, there is a great untapped opportunity within WPP to improve how we operate and the results we are able to produce for our clients.

Horizontality is the means of unlocking that value. In some respects it is frustrating that we are only at the beginning of the journey towards a more integrated WPP (I have never been a patient person). Fundamentally, though, it is good news. It means we still have a lot of fuel in the tank.

Our collective effort, collective strength and, above all, collective intelligence will be a growing source of advantage over new and existing rivals. On their own, WPP’s companies are formidable. Together, they become a competitor few can ever challenge.

In the meantime, remember…

- The next one billion middle-class consumers will come from Asia Pacific, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East and Central and Eastern Europe.

- Given falling birth and death rates, talent will become the scarcest resource.

- There is a need for ‘Third Forces’ to challenge the digital dominance of Google and Facebook.

- Amazon and Alibaba are becoming the online Walmart of the future.

- Internal communications are one of the keys to strategic alignment.

- Internal organisations are being built globally and locally.

- Finance and procurement are looking at marketing as a ‘cost’ not an investment.

- Government is becoming a more important potential client.

- Sustainability is the core of long-term strategic success.

- Short-term pressures will increase consolidations and convergence.