Art of the street

O

ver the years, WPP’s Annual Reports have drawn visual inspiration from different geographical markets important to our clients and our companies. In turn, we have embraced artists from India, China, Africa, Brazil, the US, Eastern Europe, the UK, Indonesia, Mexico and last year – as the first major international communications services group to have a presence on the island – we looked to Cuba.

While the UK may have chosen to leave the EU, Continental Europe is more important than ever to WPP. More than 30,000 of our people work in Western Continental Europe, which includes three of our top 10 markets worldwide, and many of our people in Britain are non-UK EU nationals. This year’s choice of artwork recognises that fact, and celebrates the ever-stronger connections with our European colleagues, partners and clients.

In that spirit, we have taken our cue from Western Europe – focusing on Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the UK – as seen through the eyes of some of the most engaging street artists currently enlivening our city walls. For once, these are walls that unite not divide.

T

here’s a case to be made for street

art being one of the most important artistic movements of the 21st century. The world over, it is reclaiming and redefining urban space

with clever, confident, compelling imagery.

For this Annual Report, we are featuring work by 13

of today’s leading street artists. Their subject matter may vary, but they are united by a desire to take art out of its museum setting and on to the streets for all to see.

The movement has its roots in history, in the Ice Age paintings – on ceilings and walls – at the caves of Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain.

Yet street art is a highly-contemporary practice, facilitated by two key factors. First, rapid urbanisation, which has meant an ever-growing ‘canvas’ of grey city settings waiting to be adorned. Second, the rise of social media, which has created a buzz around artists and locations, making local works globally celebrated.

The art reproduced in this report can be found

across Western Europe, in Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the UK.

Frenchmen Dominique Antony and Patrick Commecy use trompe-l’œil to trick the viewer into thinking they

are seeing things that aren’t there. Those include a giant wave on the wall of a beach house on the Bay of Biscay;

and a collection of local French celebrities at balconies

or windows on the wall of a three-storey building

in Montpellier.

Bristol’s JPS does something similar with a cat painted on a wall. In a neat piece of optical illusion, it seems to

be walking towards us along an actual chain beneath its feet, which stretches out from the wall.

In street art, size matters. Its makers tend to use the very large space on an urban wall to paint very large subjects: two pairs of twins from Italy’s Agostino Iacurci;

a blonde comic-book heroine, inspired by Roy Lichtenstein, in the case of Stepan Krasnov; and a couple of pouting silver-screen icons by Rone.

OAKOAK, of Saint-Étienne, however, bucks that trend, preferring a smaller scale, with touches of visual whimsy and a keen eye for detail. He hones in on architectural features such as peeling paint, which most of us would barely register. For his two works in this report, he deployed the bars of a tiny ventilation shaft to represent

the stripes of a zebra; and the horizontal crack in a wall

as a horizon in the desert, on which he drew tiny camels.

What unites all 13 of our chosen artists is that their imagery is figurative: something that’s true of most street art. It’s a movement that aims to communicate its message fast – where the viewer doesn’t need to be steeped in

art history.

The work is accessible to all people in all places: such

as Florentine artist Exit Enter’s image of a stick man grabbing on to a red heart that’s about to fly away; and

Jef Aérosol’s Nuée de papillons, in which a young boy throws a swarm of butterflies into the sky.

Often relying on visual puns or double

takes, street art doesn’t demand linguistic understanding either. It bridges cultures, borders and also dictionaries. It gives sometimes harsh environments a sense of place and community.

Certain artists use recurring characters. XOOOOX achieves this with his introspective fashion models; as does Nick Walker with his artist-gentleman, in bowler hat and pin-striped suit, regularly depicted in the act of creating a piece of street art.

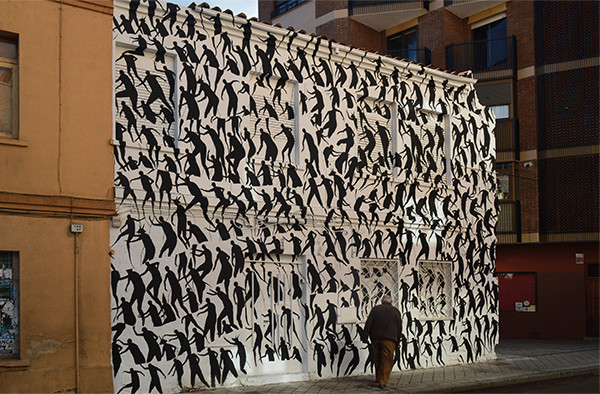

Many times, of course, works invite the viewer to stop and reflect. David de la Mano,

for example, with Diaspora, in which a black mass of silhouetted humans – with flippers for legs – appear to be taking flight. His fellow Spaniard, Pablo S. Herrero, uses bare trees

that seem to suggest nature reclaiming the

streets ever so slowly from metropolitan forces.

All 13 of these artists, then, are

transforming urban environments across

the continent. They combine wit, a gift for communicating with large audiences and a position at the cutting edge of today’s art.

These are walls, but ones that bring people together rather than divide.

Mark Seliger

Mark Seliger is a well-known American photographer noted for his portraiture. His credits include Rolling Stone, where he was chief photographer for 10 years, shooting over

125 covers. In 2001 he moved to Condé Nast. He shoots frequently for Vanity Fair, Details, Italian Vogue, German Vogue among others. His work has been exhibited in museums and galleries.

Gallery

Rone

Whispers

Stepan Krasnov

Dream

Dominique Antony

La grande vague (The great wave)

A.FRESCO, Patrick Commecy

Juliette et les esprits (Juliette and the spirits)

Nick Walker

Love Vandal

Agostino Iacurci

Siamese

Exit Enter

Love is the exit

JPS

Untitled

XOOOOX

Untitled

David de la Mano

Diaspora

Jef Aérosol

Nuée de papillons (Cloud of butterflies)

Pablo S. Herrero

Brecha (Opening)

OAKOAK

La caravane passe (The caravan goes by)

OAKOAK

Urban zebra